– By Virginia Alberdi Benítez –

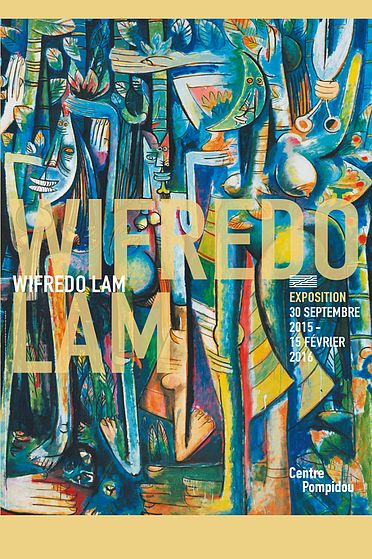

As time passes, Wifredo Lam confirms his status as one of the most secure values of the Cuban Visual Arts in the global context and remains an essential reference of the vanguards of the Twentieth century.

A prevailing trend among art historians, that classifies artistic results in schools and aesthetic trends, often includes Lam within the Surrealist movement. But a close look at his work, taking into account its evolution and the internal dynamics of the images captured in many different formats, will show an irreducible originality, convincing and dazzling at the same time.

André Breton himself, the guru of the surrealist movement, was who earlier noticed how the Cuban painter overflowed the assumptions of that vanguard: “Nobody but my friend Lam has produced, with such simplicity, the unity of the objective world and the magic world. Nobody but he has discovered the secret of physical perception and mental representation, qualities that we have tirelessly sought in surrealism, because the greatest drama of modern consciousness arises from the growing separation of these abilities”

This intense relationship between dream and reality, between the earthly and the imagined visions, goes through each one of the pieces exhibited since last September to next February in the comprehensive retrospective which these days occupies the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris.

It is the first time that the French institution dedicates an exhibition entirely devoted to the Cuban master. They gathered 300 works including paintings, drawings, prints and ceramic pieces, from public and private collections.

Earlier in 2015, the Pompidou Center exhibited some of the pieces created in France by Lam in occasion of an exhibition in honor of Michel Leiris, where the Cuban artist cohabited with works by Picasso, Bacon, Giacometti, Masson and Miró. The new series of Lam in Europe will continue in 2016 with other personal exhibitions at the Tate Gallery, in London; and the Reina Sofia Center, in Madrid.

People visiting Havana should not miss the works of Lam exhibited in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, especially La silla (The Chair). This painting completes the vision of one of the highlights of his career, considering the links between that piece of art, and perhaps his most reproduced and cited work, La Jungla (The Jungle), from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, in New York City.

Both paintings were born from the encounter of the artist with the Cuban reality in the 40s of last century, after Lam was back from his first and long European experience. He was born in Sagua la Grande, a town on the northern coast of the central region of Cuba, the son of a Chinese immigrant from Guangdong and a Cuban mixed-race descendant from black slaves and ruined Spanish colonists. While his father went on Sundays to join his expatriate countrymen, little Wifredo escaped to a vicinity house where a black community worshiped their transplanted African deities through drumming, dancing and ritual songs that preceded a profane festive celebration.

Young Lam discovered his artistic vocation for painting. “I do not know what has occurred that I paint. I think I was born a painter. This is a rather mysterious vocation, and from my youngest age I realized that, it could not be anything but a painter or a poet. However, in some order, I’ve been an abandoned individual, because I was born where nobody talked about painting or the things around this occupation. I paint since I was six years old and I was so anxious to do that I forgot everything else. I painted portraits and landscapes, but I never painted as a child. My concern for painting was, in general, much deeper,” the artist confessed to the journalist Fernando Rodriguez Sosa in 1980.

In 1916 he moved with his family to Havana, attended irregularly “San Alejandro Academy” and went to the Hall of the Association of Painters and Sculptors, in the Cuban capital. This made possible that he received a small amount of money granted by the municipality of Sagua, what the government of the time offered to relieve the needs of the “colored people with artistic talent” to travel to Spain in 1923, where he visited the Prado Museum and closely monitored the artistic renewal that took place in France and Germany.

The death of his first wife and young son in 1931 introduced a dramatic notion in his painting, in his maternities and portraits. The support of his paintings is at always the paper, motivated by economic reasons of somebody who lived a life full of poverty.

In 1937 he settled in Paris; he met Picasso, cultivated the friendship of André Breton, he exhibited with the Surrealists, visited the ‘Musée de l’Homme’ to admire ethnographic African art samples. The human faces of his compositions became echoes of ritual masks. The revelation of aesthetic maturity was then just around the corner.

After returning to Cuba in 1941, forced by the outbreak of World War II, Lam rediscovered his roots and painted several of his masterpieces. Before leaving Paris, he had illustrated the first edition of the poetry book Cuaderno de retorno al país natal (Notebook of the return to the homeland), by Aime Cesaire, from Martinique Then, the artistic was recognized as a Caribbean, than as a Cuban man.

In Havana he met the anthropologist Fernando Ortiz, who had established the concept of transcultural movement into the world of the Cuban identity. He was also in contact with the ethnologist Lydia Cabrera and her testimonial records of traces of Yoruba culture on the island.

From those experiences, Lam´s painting found a rare and explosive balance between the reflection of the telluric forces in the construction of its identifying features and expressive codes coined by Western modernity.

About that growth of the artist’s work, the poet Miguel Barnet said: “The work of Lam is the woodland, it is the jungle, the jungle as he defined it, and the elements of the jungle in this work are the jungle sticks, the stones, you can smell of sap from these roots. And this is very important because until then, people in Cuba had not really taken this factor nurturing our culture into account, that source so important in our culture, that is why Don Fernando Ortiz is interested in part in the work of Wifredo Lam and makes what is for me, the most meridian, the most luminous essay clarifying Lam’s work, maybe not so much from the point of view of the treatment of the plastic subject, but from an anthropological point of view. “

If it is necessary to find a relationship in his work, it must point to what was being discovered in writing by his compatriot Alejo Carpentier (magical realism) and in music by the Brazilian Heitor Villa – Lobos. It is no coincidence that in a written text about Lam in 1954, the Spanish poet and essayist Maria Zambrano, who lived in Cuba, did note that “the world of the tropics is not plastic, it is musical, it is orphic; Lam´s painting reveals its secrets; his paintings possess a rhythmic distribution. “ Regarding this, Lam himself agreed, as when asked to explain the contents of La jungla, he said; “Many people ask me what is the meaning of each of the elements of the picture. For example, for the body, I was inspired by sugarcane, which is the focus of our economy. But, every time you look at this painting, it can be interpreted differently. I think it’s quite appealing to the tropics, it’s like a symphony. Of course, I cannot explain it note by note, as for sensitive ears like for sensitive eyes, there is a poem hidden in the painting.”

That quality has been developing with time. Ritual marks, geometric configurations, traces of vegetation, creatures guessed between myth and reality form a recognizable and authentic imagery, consistently cultivated until Lam´s last years. He died in France in 1982, but his ashes rest in Havana.

About the articulation between Cuban identity and the universality of the artist, the words of the Cuban critic Nelson Herrera Ysla are really worthy: “Wifredo Lam moved away from any stereotype, formula or scheme to try to sweeten or deform the hybrid, mixed culture, to which he belonged by blood, family background and heritage, and he knew how to take the best qualities of other cultures in the world.”