We applaud the article about Ernesto García Peña in granma.cu. It shows that Ernesto is well known an loved in Cuba and postulates that the development of the artist lies not so much in experimentations rather that the real adventure of his art lies literally translated: ‘in the purification of style and image decanting’.

Ernesto García Peña in his Studio

Ernesto García Peña – Produced by ARTEX

CUBA –USA: autopista en las artes visuales

Por Virginia Alberdi Benítez

La presencia de las artes plásticas cubanas en Estados Unidos en el último medio siglo puede compararse con el tránsito por una autopista, a veces interrumpida por grandes obstáculos, pero nunca cerrada al paso de los vehículos.

Indudablemente la nueva etapa de las relaciones entre ambos países, abierta el 17 de diciembre de 2014 con el anuncio del restablecimiento de vínculos diplomáticos y afianzada con la reapertura de embajadas en Washington el 20 de julio de 2015 y La Habana el 14 de agosto de este mismo año, debe favorecer un flujo mayor de artistas y exposiciones en lo adelante.

En el ámbito cultural es mucho más previsible un entendimiento cercano a la normalización de las relaciones que en otros espacios. Son muchas y muy notables las diferencias y los puntos de vista sobre funcionamiento democrático, derechos humanos y perspectivas geopolíticas.

Para los cubanos que viven en la isla la gran asignatura pendiente es el levantamiento del bloqueo económico y financiero impuesto por los gobiernos de Estados Unidos contra Cuba.

Sin embargo, a partir de la adopción por el Congreso de EE.UU. en 1989 de la Enmienda Berman se flexibilizaron algunos términos del bloqueo para favorecer los intercambios culturales. De tal modo se permitió a ciudadanos norteamericanos adquirir obras de arte y materiales informativos como excepción, amparándose en derechos constitucionales.

Fue así que galeristas y coleccionistas comenzaron a visitar la isla y comprar y representar a artistas cubanos. En la actualidad resultan muy activas algunas galerías especializadas en arte cubano, como la Magnan Metz y la Marlborogh, ambas de Nueva York, en tanto sigue incrementándose la prestigiosa Colección Faber, cuyas exposiciones llaman la atención de especialistas.

Miami, y en general, el sur de la Florida, ofrecen un panorama muy particular, determinado por la influencia de la comunidad cubana más numerosa en el exterior. Desde el Museo de Arte Cubano, la Fundaciòn Cisneros-Fontanals y el Pérez Art Museum hasta decenas de galerías de muy diversa escala (una de las más prominentes es la Cernuda Arte), la exhibición y comercialización de obras de arte de creadores residentes en la isla se ha ido convirtiendo en parte consustancial de la vida de ese enclave.

Desde 1972 el Centro de Estudios Cubanos, de Nueva York, bajo la dirección de Sandra Levinson, había propiciado, hasta donde fue posible en medio de las tensiones políticas, la difusión de publicaciones y producciones artísticas. Pero a partir de 1999, con la creación del Cuban Art Space, el Centro multiplicó su espectro promocional y comercial, con el aval de la Enmienda Berman.

Fue noticia en el año 2000 la exhibición en el Museo Latinoamericano de Long Beach y luego en el Museo de la Universidad de California de la que hasta ese momento constituyó la más nutrida muestra de artistas cubanos de la nueva generación en Estados Unidos.

Se trataba de recuperar el terreno perdido ante el interés con que por esos años instituciones y coleccionistas europeos, como la alemana Fundación Ludwig (que, por cierto, abrió una sede en La Habana) se habían aproximado a los artistas cubanos formados en las escuelas durante el período postrevolucionario.

En realidad, algunos de estos eran ya conocidos en los circuitos norteamericanos, por haber emigrado hacia ese país a partir de la crisis que estremeció la isla en los 90. Pero no todos pudieron insertarse con éxito en ese mercado como lo hicieron José Bedia y Tomás Sánchez.

Otros comenzaron a beneficiarse de becas y bolsas de viaje otorgados por instituciones académicas norteamericanas y comenzó a ser frecuente, a partir de la primera década del nuevo siglo, la huella de artistas procedentes de la isla en los circuitos de exhibición de ese país. Tempranamente Roberto Fabelo había dado la clarinada en 1993 al conquistar el premio en la Bienal Internacional de Dibujo de Cleveland, pero él mismo solo logró un significativo posicionamiento cuando en 2014 desplegó su obra en el Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Long Beach.

Entre los creadores de mayor impacto público en el último lustro se cuentan Carlos Garaicoa, con su exposición en el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Los Ángeles: Alexandre Arrechea, quien intervino en 2013 varios de los icónicos edificios de Park Avenue, en Nueva York; y Los Carpinteros, con su instalación en el Armory Art Show, también de Nueva York.

Otro indicador a tomar en cuenta son las subastas. Los valores más establecidos siguen siendo los pintores de la vieja guardia, ya desaparecidos, como Wifredo Lam, Amelia Peláez, Cundo Bermudez y Mario Carreño. Pero en los últimos años se han dado sorpresas: en 2013 Tomás Sánchez en Christie’s vendió dos obras por más de medio millón de dólares.

Al ser interrogado sobre las perspectivas que se abren al arte cubano con la reanudación de relaciones diplomáticas entre Cuba y Estados Unidos, el experto Alex Rosenberg, opinó: “Estos cambios traerán como consecuencia un aumento considerable en los precios de las piezas de artistas que viven y trabajan en Cuba. Pero también creo que con el tiempo desaparecerá paulatinamente la sensación de novedad que representa Cuba para el mercado norteamericano, y que entonces los precios comenzaran a estabilizarse. Lógicamente, si aumenta el turismo, aumentará la venta de arte cubano. No creo que los artistas que ahora tienen éxito puedan vender mucho más, puesto que ya venden la mayor parte de lo que hacen. Tampoco creo que el turismo afecte su arte seriamente. Los principales beneficiados serán los artistas menos exitosos que ahora podrán vender a un público mucho más amplio y menos sofisticado”.

Ernesto García Peña – Island Lyrics

The Poetry of Dreams

DOLORES DENARO – Art Historian and Curator –

Ernesto García Peña (Matanzas, Cuba, 1949) belongs to the first post-revolutionary generation of Cuban artists. The long list of his exhibitions reflects the fact that he is recognized in Cuba as one of the best known and respected artists of his country. Upon completing his studies at the Academy in Havana, he remained as a professor and for many years influenced the generations that followed.

The motifs of his paintings – as evidenced by the title of the exhibition and of the present catalogue – resemble lyrical poetry. Each work is a poem marked by the lyricism and the visual language of dreams, featuring imagination and intuition at its core. Visually, the works are marked by an aesthetic of delicacy and oscillate between the surreal and the abstract. García Peña uses acrylic paint like watercolor and, by aqueous application of the acrylic on the surface with paint brushes and flat brushes, obtains a transparency that is full of light.

The different elements are presented on the canvas as a breeze or distant memory. The paintings nourish from this delicate and yet radiant coloring – mainly in shades of blue, gray or red – from the empty spaces that reveal the beige background, as well as from the overlap of the layers that are often complemented with drawings from above or below. García Peña is “an artist of atmospheres of subtle transparencies…”, which are the result of “a long road of searches and explorations”.1

SEARCH FOR BEAUTY AND HARMONY

The artist focuses on transmitting his emotions and fantasies around hedonistic topics. At the core is the ethi- cal principle of the search of sensual pleasure and enjoyment. His work is an obsessive search of beauty and harmony, however he discloses very little about the content of his creations. He leaves the interpretation of his motifs to the viewers. The titles of the paintings provide a clue towards a possible reading of the artist’s intent since García Peña names his work after completion.

Cuando todo comienza (When Everything Begins) shows two hills that represent the oversized breasts of a woman. On one of them lies a naked masculine figure in profile, with eyes closed. He seems to be crawling towards the nipple on his thorax, devotedly inhaling the oncoming fragrance. The stylized igniting spark emerging from one of the nipples recalls the first hours of human life, when the female breast develops from a sensual feminine organ into the first source of nourishment for every human being.

In general, the enigmatic female nude is present in all of García Peña’s works. In El ritual de… (The Ritual of…,), the sensual body of a naked woman seems to be floating between the sky, the water, and the landscape. Only upon a second look it becomes apparent that there is another, smaller erotic female figure in opposite direction within the first. In Amaneceres (Daybreaks) with a similar motif, an androgynous figure lies in ecstasy between the breasts, while above float two other bodies, intertwined.

IDYLLIC SCENES

Overlapping bodies of different dimensions are a typical feature of García Peña’s works. Similarly, erotic scenes are in all his creations – some with stylized feminine nudes and others with couples floating freely on the image surface. The fragility of love is expressed in accordance with the subtly indulgent application of color. Images of “beautiful” dreams are also always idylls, i.e., harmoniously clarified motifs that influence the spectator in a nice and peaceful way. The idylls, in turn, are illusions threatened at the same time by disillusion.

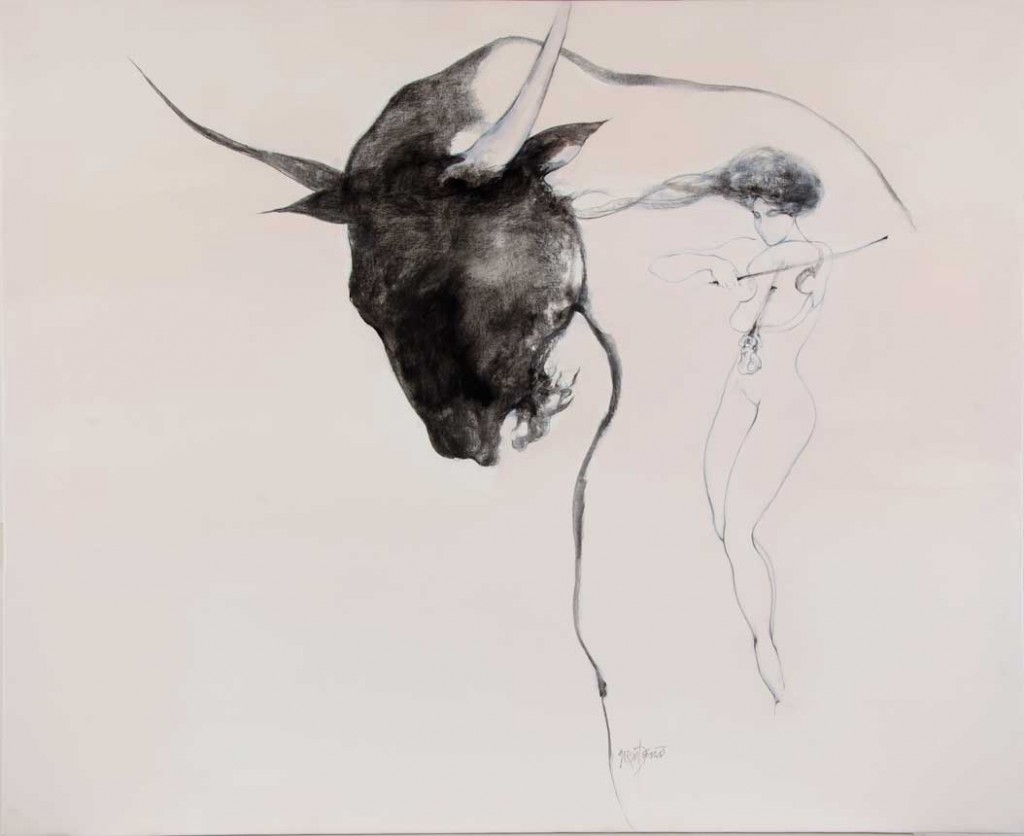

The bull and (more often) the horse, serve the artist as allegories of passion, movement, and virility. While in European iconography the symbolism of the horse depends essentially upon its color – white meaning bearer of light and black, death and ruin2– the Cuban artist is much more interested in the strength and energy that are inherent to this animal. In Móntate y… (Mount and…) a naked woman is levitating with her arms extended backwards within a huge horse head. She is sitting on the shoulders of an equally naked man, who holds her around her legs.

She obviously enjoys the state of unrestrained freedom, as if she was sitting with windswept hair on the bow of a vessel gliding over the sea. On the nape of the horse lies another couple, one person on top of the other, while from the torso an androgynous figure with wings rises toward them.

El último canto de la bestia (The Last Song of the Beast) shows a stylized feminine figure playing the violin within the body of a bull, If one understands the bull as masculine, one might be tempted to recall the story of creation in the Holy Scriptures, in which Eve – depending on the translation – was created from a bone (a rib) of Adam.

ISLAND LYRICS

Generally, Ernesto García Peña works in parallel on several paintings, so that the temporal and visual distance with a painting motif may mature in the artist’s conception. Usually, when he stands before the blank canvas, he already has concrete concepts of what he is going to paint. Later he lets himself be carried away in the process by his in- tuitions. He attempts not to follow predefined processes or procedures in order not to bind or restrict himself. However, he sometimes uses ideas he had before, or resorts to one he had already drawn or sketched at an earlier occasion. The time he takes to complete a painting – which he frequently produces as part of a series – varies according to its development. And, analogous to poetry, short rhymes or longer poems arise, all created in the Caribbean island.

1 According to Cuban art critic Virginia Alberdi. See text on the invitation card to the present exhibition of García Peña in Arte- Morfosis Gallery.

2 See encyclopedia of the iconography: www.beyars.com/kunstlexikon/lexikon_8834.html