ArteMorfosis is happy to share Virginia Alberdi’s article on Gilberto Frometa’s visit to Zürich as published in the online and paper editions of granma on November 12, 2015

Abstract and Different

By Virginia Alberdi Benítez; Translation by Luz María Rodríguez Cabral –

With the presence of the paintings by Gilberto Frómeta in the ArteMorfosis gallery, in Zürich, this November, the art lovers of Switzerland and other countries that visit this singular space for the promotion of the contemporary Cuban art have the opportunity of having access, not only to the creations by one of the most active and consistent painters inside and outside Cuba, but also to the impact of Abstraction, one of the aesthetic tendencies from the artistic avant-garde of the XX Century on the Caribbean island.

Above all, this exhibition should beat prejudices about the cultural reality predominating in a country that adopted Socialism as social system from 1961. In the experience of the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death and of most of the East Europe states created after the defeat of Fascism during the Second World War, as much East Abstraction and other renovating tendencies of Western art were excluded.

In Cuba, the so-called “Socialist realism” was never an official doctrine. On the contrary, a favorable climate was guaranteed to the widest aesthetic options from the beginning, with some tensions in certain moments, but with wide margins of institutional visibility for critical statements.

The Abstraction style emerged about 1910 and according to its consequences has become one of the most significant expressions in the spirit of the XX century. It had set up in Cuba from the fifties, before the rebellious forces entered in Havana in January 1959. However, valuable precedents are found in the work of the avant-garde artists Amelia Pelaez, Marcelo Pogolotti and José Manuel Acosta.

Their imprint was observed from the proximity to the movement that was strengthened in the United States after the end of the war. To be apart from the avant-garde that had appeared in the island from the last 20s to the 50s and showed identity signs through codes similar to the European codes, those artists, pioneers of the Abstraction in Cuba, were inspired by the American Abstract expressionists more than by the European lessons of Mondrian, Leger and Picabia. In fact, a painter of Cuban origin, Julio Girona, resident in the United States and a soldier in Second World War, after returning from the battle fields became affiliated to the abstract art in its informal version.

Seven painters and four sculptors started in April of 1953 when they gathered their works in La Rampa gallery in Havana, an area characterized by constructions of the Modern Movement. This group adopted the generic name of The Eleven: Guido Llinás, Hugo Consuegra,Vila, Antonio Vidal, Fayad Jamis, Tomás Oliva, Agustín Cárdenas, Antonio Díaz Peláez, Francisco Antigua, Viredo Espinosa and José Ignacio Bermúdez, these two last two had an ephemeral stay in the group In the second exhibition, the group included Raúl Martínez, a youth that had just been in the Institute of Design of Chicago and who better translated to his own language the essence of the abstract expressionism before entering with remarkable success in the pop art.

About The Group of the Eleven, Antonio Vidal left the following testimony: “The Group of the Eleven was the result of an encounter of generations. We gathered because we were young and we wanted to break up with what preceded us. We were a group of idealists and we created an art that was not sold and that was not interesting for most of the people. In fact, each one of us had traced his own way, without having any agreement, since we never made a manifesto or called ourselves “The Group of the Eleven”. However, we did have similar ideas on creation because what we really wanted was to make a different art. We were influenced by the North American painting that some of us knew by the Goya and Art News Journals.”

ANTONIO VIDAL: Mirada (Source: thecubanhistory.com)

For the following years, the nucleus of The Group of the Eleven turned around Hugo Consuegra, Antonio Vidal, Guido Llinás and Tomás Oliva. Later, Manolo Vidal, Antonia Eiriz, Juan Tapia Ruano and José Rosabal joined in the late 50s. In the abstract orbit, for their bill, they rotated in a certain time, Roberto Diago and Mario Carreño were in the abstract orbit by their own way.

Another interesting landmark was marked by the Group of Ten Concrete Painters that exhibit for the first time in 1958. It was initially composed by Loló Soldevilla, Rafcaael Soriano. Luis Martínez Pedro, Salvador Corratgé, Wilfredo Arcay, Pedro Álvarez, Pedro de Oraá, José Mijares, Sandú Darié and José Menocal. Corratgé said about the genesis of the group: “We also met at Loló Soldevilla’s home. She was a woman that economically helped us very much. She had been a Cultural Consultant of Cuba in France. After the coup d’état in 1952, she returned to Cuba with a great source of information. She brought many books and through her, those of us that didn’t have many possibilities, were updated, differently from Martínez Pedro and Sandu Darié who already had relationships with the French contemporary movements. Loló brought reproductions of Vassarely and of other concrete painters, she herself created geometric painting, and when she showed us the catalogs, to talk to us about the movement existing in Paris, many of us became interested and I myself became enthusiastic about this style of painting.”

Some of the Group of the Eleven and some of the Concrete Painters stayed faithful to their aesthetic beliefs in the middle of the sociocultural transformations that occurred after the drastic political change that took place in Cuba in the 60s. For some people, the abstraction, elements; Antonia Eiriz turned toward a new figuration of expressionist character, Martínez Pedro moved to Optical art and Sandú Darie turned to the Kinetic art. But, for others, like Salvador Corratgé, José Rosabal, Díaz Peláez, Antonio Vidal and Pedro de Oraá – the last two received the National Award of Visual Arts for the work of their whole life- the aesthetic filiation remained unchanged. The internationally well-known sculptor Agustín Cárdenas developed his career in France, but he has kept an unbreakable bond with his homeland.

Pedro de Oraá, Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas 2015: untitled, mixed media on canvas (source: ecured.cu)

Around 1979, there was a new group, the Cuban Group for Optical Art, integrated by a quartet: Ernesto Briel, Jorge Fornés, Helena Serrano and Armando Morales. But the predominant thing has been the emergency of painters that are themselves convinced that they have expressive personal possibilities in the multiple areas of abstraction

In such a sense, there has been some kind of a generational continuity, among creators, such as Carlos Trillo, Minerva López, Raúl Santoserpa and Juan Vázquez Martin, Gilberto Frómeta, Julia Valdés, Alberto Lescay and the sculptor José Villa, who, in spite of being known by his representations of historical and artistic figures, has an impressive repertoire of abstract works.

It is curious that amid the conceptual and postmodern waves of the last decades of the last century, the abstraction has been present in the works of the very young Carlos García de la Nuez, Eduardo Rubén, the sculptor Tomás Lara, and occasionally, in Flavio Garciandía.

At the crossing from one century to the other, when abstraction was strongly revaluated by the Cuban artists, the work of Rigoberto Mena, Jorge Luis Santos, Manolo Comas and Andy Rivero were highly estimated, and already in the current century, are leaders Ronaldo Encarnacion, Enrique Báster, Danilo Vinardell, Bárbaro Reyes (Pango) y Reyner Ferrer are leaders.

Rigoberto Mena, untitled, 2012, Mixed media on canvas (source: rigobertomena.com)

In this quick overview. we cannot ignore an event: the opening in 2011 of the exhibition La otra realidad: una historia del arte abstract cubano (The Other Reality: A History of Cuban Abstract Art) in the National Museum of Fine Arts (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes), which brought together works by Cuban abstract artists created for more six decades, all under the curatorial criterion of Elsa Vega.

Important personal and group exhibitions were held in La Acacia Gallery, at the Wilfredo Lam Center (Abstract May), and in different institutions linked to culture. Abstraction has also occupied spaces at the Biennial of Havana. Some examples: In the Eighth Biennial, the exhibition Abstracción viva (Live Abstraction) was shown (at the Center for Preservation, Restoration and Museology, CENCREM); in the Eleventh Biennial, there was the exhibition De lo vivo a lo pinta´o (From live to painted), and most recently, in the Twelfth, Gritos del silence ( Shouts of Silence), and also several individual exhibitions, such as: Mi segunda piel (My second skin), by Julia Valdés; Overwhelm, By Enrique Báster; Inventario (Inventory), by Carlos A. García de la Nuez; Through, by Carlos Llanes; RAK 4200, by Rigoberto Mena; Abstractivos, by Pedro de Oraá, Rompecabezas (Puzzle), by Andy Rivero; Made in Cuba, by Juan Arel; Work in Progress, by Jorge Luis Santos; the collective exhibition of photography Quiero ser lo que puedas ver (I want to be what you can see), and some of the sculptures of the Exhibition Perfiles de Acero (Steel Profiles). All these in the macro-exhibition Zona Franca in the Morro Cabaña complex.

Havana, November 2015

Gilberto Frometa – Tropical Light

Colorful Images of the Subconscious Identity

On the Abstract Visual Language of Gilberto Frómeta

DOLORES DENARO – Art Historian and Curator –

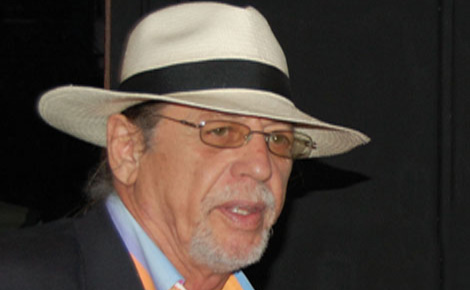

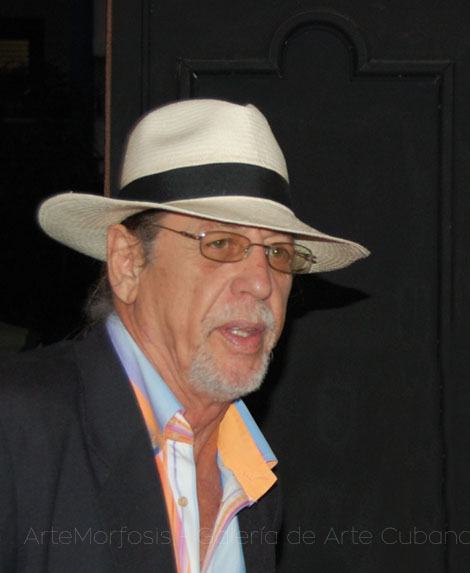

Gilberto Frómeta (Havana, Cuba, 1946), the third artist presented by the ArteMorfosis Gallery in 2015, is also part of the first generation of post-revolutionary Cuban artists. He was initially known in the Caribbean island state, and later internationally, for his images of horses painted in black on a white background. However, the focus of the artist’s first Swiss exhibition Tropical Light is the abstract painting that has appeared in his work since 2001. A selection of powerful color paintings from the years 2005 to 2015 are presented.

The artist offers the following explanation of why and how he evolved from the initially monochromatic realistic themes to the strongly colored abstraction: “I reached abstraction because I wanted to include color in my works. My previous work had been monochromatic for many years. Until then I had feared that colors would make my paintings frivolous. That is how I arrived at abstract expressionism without having a specific artist as ideal. At the same time I observed children scribbling when they learn to hold a pencil as well as the airbrush painting technique. Overall, the road to abstraction was a culinary act that lasted several years.“1 The liberation from realistic painting to abstraction is an evident step, and said development may be retraced in his work.

While the horses in the black and white drawings and the works on paper in black ink from the early years were often inspired by photographs, the transition to abstraction and to the color palette allowed him greater freedom of artistic expression. In 1987 the first abstract horse head appeared in the painting Celos (Jealousy) which, in addition to black, also contains red. In 1993/94 Frómeta began to work with acrylic colors, and the horses first became increasingly surrealist and then abstract. Newly added is the non finito. That is, he takes the liberty of leaving subjects unfinished. Consequently, the successive motifs were increasingly more abstract. In Daring (2001), he presented his first abstract horse – a brightly hued painting of intense colors in different tones of blue with a red accent. Starting then, the artist concentrated for several years on the development of non-figurative painting.

There followed numerous color experiments with the airbrush, dripping and scraping techniques and action painting. In the act of painting, in applying layer over layer of industrial colors – acrylic on the bottom and oil above – he now employs the most diverse tools such as paintbrushes, spatulas, mason’s trowels, brushes or whatever is at hand. His aim is to highlight the unknown, the subconscious.

In contrast, the titles of the works, which in most cases he designates after the paintings have been completed, limit the viewer’s reading of the images or lead them in a specific direction. So, for example, due to its application and structure, which resemble drops, we easily understand the light gray color layer on top in the 2005 painting Rain as water running down the window when it rains. The red, blue and yellow paint layers that remain below and their partially transparent brown and green mixed shades enable us to see the artist’s free working spirit. In certain places the colors have been eliminated or removed using different tools, as if the surface had been damaged. Above, on the right side of the painting, one can see the eye of a horse, which confirms that Frómeta had painted over one of his horse paintings. On numerous occasions he painted over his works in that way during his four-year stay in China.2 With this process the artist liberated himself of the horse, his inspiration for many years, which he sees as man’s best friend. His fascination with the powerful animal, without which the western man could not have achieved everything he has created (think of agriculture, the first means of transportation and construction) has remained until today.

As stated by Frómeta himself, his abstract works should be regarded as a continuation of abstract expressionism. This artistic style developed in the United States from the early 1940’s through the early 1960’s with Jackson Pollock (action painting) and Barnett Newmann and Mark Rothko (color fields) as main representatives. As in their case, the Cuban artist’s interests lie in the expressive creation of the subconscious. The artistic trend of abstract expressionism, although initially disliked by the conservative sector in the U.S., was used in exhibitions during the cold war as a means to present the United States as a modern, liberal country. Presumably because of this, abstract art was not recognized and even considered too imperialistic for decades 5 after the revolution in Cuba. Only in recent years has abstract art been accepted officially in Cuba, and now enjoys increasing popularity. Some Cuban artists saw in it the opportunity to achieve success rapidly, because they assumed that abstract motifs have a merely decorative role.3 In Frómeta’s work it is not so much a question of aesthetic beauty as of the visualization of the unconscious identity.

Cuban Raúl Martínez (1927-1995), Chinese (Shanghai) resident Xiaobai Su (1949) and Spanish artist Antoni Tàpies (1923-2012) are painters who have impressed Frómeta on his road to abstraction. By the way, Tàpies, who has been praised as one of the great artists of last century and genius of abstraction, contrary to the opinion of many art critics, did not see himself as an abstact artist but as a “realist who sees his work as an attempt to capture reality and represent it for the observer“. Perhaps the concrete titles of Frómeta’s abstract paintings should be understood in this way. Of course, he is also familiar with the works of Vassily Kandinsky, the pioneer of abstract art. And although he ignores the contents of Kandinsky’s theoretical works, Frómeta’s paintings recall his thoughts, as expressed in Kandinsky‘s essay Über das Geistige in der Kunst (About the Spiritual in Art), first published in 1912. In it, the Russian artist defined, among other things, three types of images: impressions, improvisations and compositions.4 Accordingly, the compositions emerge from the subconscious. Such abstract painting, whether constructed consciously or subconsciously, is a composition of structures, colors and shapes (or non-shapes), and the distances between them. Frómeta’s abstractions, developed in the island state without the possibility of outside influence, are alive with bright colors. For him, color is, “the most universal language that reaches and directly affects all layers of society.“5 Or as formulated by Kadinsky, color touches the soul and makes it vibrate, for Frómeta, in the clear tropical light.

—

1 Author’s e-mail interview with the artist in September 2015.

2 Thanks to his horse images, the Cuban artist was invited to exhibit in China.

3 Alex Fleites, Work in Movement, manuscript, www.pinturagfrometa.com/gilberto_frometa/?en_remarks,18

4 In: Wassily Kandinsky, Über das Geistige in der Kunst. Insbesondere in der Malerei. Originalausgabe von 1912, 3. Auflage, München: R. PIPER & CO., VERLAG, S. 29.

5 Author’s e-mail interview with the artist in September 2015.

Dolores Denaro, born in 1971, read Modern Art History, Architectural History, and Monument Preservation as well as Religious Studies at the University of Bern. She holds an MA in Cultural Management from the University of Basel. Until 2001 she was freelance publicist and curator as well as research assistant at the Paul-Klee-Stiftung and later the Johannes-Itten-Stiftung at Kunstmuseum Bern. From 1999 until 2001 director and curator at Kunsthaus Grenchen. From 2002 until the end of 2011 (ten years) director and curator at Kunsthaus CentrePasquArt in Biel. From 2012 until 2013 external expert consultant for the Julius Bar Kunstsammlung (art collection). Since 2012, president of the Swiss national Kiefer Hablitzel Preis fur bildende Kunst (fine arts award). Since 2013, freelance curator and publicist. Numerous exhibitions and publications with the focus on contemporary art as well as board member of various art foundations and jury member on several panels.

Gilberto Frómeta

The Shades of a Temperament

– RAFAEL ACOSTA DE ARRIBA –

– Poet, Essayist and Art Critic –

Gilberto Frómeta’s painting belongs to the imagination of quite a few generations of Cubans, including mine. I followed his work with interest and admiration since I was a young man interested in the visual arts; way back then I understood that his painting is an act of faith. Time went by and Frómeta became famous to critics and experts – I would say even more – one cannot write about visual arts in Cuba and ignore the poetics of this artist who is recognized to have occupied a distinctive and original place in the island’s art.

In his exhibition Tropical Light, Frómeta once more shows the mastery of his abstract painting. It should be added that he has no less expertise in figurative work, but that theme should be handled at another point. From the first glance, one recognizes in these pieces aspects of his previous work, precisely the one that made him well known in the Cuban painting scene. It could be said that it is like the elaborated sediment, the presence of a style refined with the years, or better yet, the result of maturity in its fullness now displayed in a discourse constructed for the occasion. Textures and colors, veins and arteries of the image are laid bare; stripes of colors that irrupt like cuts on the canvas surface; superimposed layers of shades and tones, drippings of colors – in short, signs of violence in the images that harmonize and attain balance in a talent that does not resist domestication by the orthodoxy of art. There is no restraint in these pieces, but indeed a sense of composition that prevents the distinctive features to overwhelm or disrupt the final result. The artist’s pure temperament is captured in each painting.

The artist’s subjectivity nourishes his style; in this case it is his emotion that dictates the strokes. The mystery of color; the cryptic nature of abstractionism encourage the poetry contained in the metamorphosis of the images in his paintings. Some works have been implanted with pieces of jute (or sack) fabric, which grants them additional uniqueness. The geometrical aspect is also present – not to define, but acting in support of the images; it is perhaps the central element of the composition.

Frómeta’s abstract painting does not ask questions about the frontiers of art, something that belongs more to the attempts of the so-called conceptual art (from Duchamp to the present); what it does is to exercise freedom of creation within those limits. Neither does it question itself about the limits of abstraction, a genre that became academic at a given point in twentieth century art. Therefore, I insist, what our artist’s abstract painting intends is to recreate to the convulsions the meta-language of abstraction. I could state that his work was always a denial of that odd idea that decreed “the death of painting”. Instead, it is a vital and expressive painting; signs ranging from the silent blue (evocation, of course, of the Caribbean Sea) to the striking red and similar, going through gradations of the dark shades – a gradual descent to the shadows, the luxury of gloom. They are signs that crescendo from the silent murmur to the uninhibited shout of Pollock.

These paintings evoke various sensations in us; one of them is the idea of infinity, often associated with abstraction. “The infinite is demonic and borders the romantic vertigo.”, said Octavio Paz in reference to twentieth century abstract painting. This assertion and my knowledge of Frómeta’s work lead me to suppose that he is one of the old school romantics, a creator in search of the totality of signs. The artist fills the empty space with blood, with fury, with the sharp remarks produced by the most passionate creation, with his character. The work features poetry of movement and transmutations of color, lyrics of a frenzy that does not stop until the conscious abandonment of the piece.

The visual discourse of Tropical Light, its essence, is rhapsodic. Gilberto Frómeta has recreated the diorama of lights of varied intensity characteristic of the Tropics in this exhibition. There is light on top of the colors and underneath them; supporting, fragmenting, and illuminating them. Light is like the latent soul of the pieces of the exhibition. The artist has chosen the solar luminosity of these latitudes and has materialized them in paintings that synthetize and express the Dionysian nature of the Caribbean Sea or of Cuban art, of which he is one of its indisputable masters.

Havana, July 2015

Frometa working on – RELIEF SYMPHONY –

Acrílico y óleo sobre lienzo / Acrylic and oil on canvas. 212 x 350 cm 2010 Signed in Beijing

Rafael Acosta de Arriba (Havana, Cuba, 1953) Art critic, poet, essayist, professor at the University of the Arts (ISA) and at the Fac- ulty of Arts and Literature of the University of Havana. Doctor in Historical Sciences (1998), and Doctor in Sciences (2009). He works as a researcher at the Juan Marinello Institute for Cultural Research in Havana. He has received several prizes and distinctions, among them, on four occasions (1994, 2010, 2012 and 2014) the Annual Prize of Research granted by the Ministry of Culture. In 2011 he received the Guy Pérez Cisneros National Prize of Art Criticism. He presided over the 7th and 8th Havana Biennials. He has lectured at conferences, postgraduate and master courses in Cuba, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Italy and Israel. He was chief editor and director of several cultural magazines. In 2005 he founded and was first director of the magazine Fotografía Cubana. From 1999 to 2005 he was President of the National Council for Visual Arts. He has been cura- tor of numerous exhibitions, both in Cuba and abroad. He has published six books of poems and seven books of essays. His essays and articles have been published in specialized magazines.