– Virginia Alberdi Benítez –

An important area of the Cuban art reveals the ethnic awareness of the inhabitants of the Antillean Island. The encounter between Africa and Europe in the creation of the Nation determines that “condition of the soul” characterized by the Cuba anthropologist Fernando Ortiz as the element essential of the Cuban character.

It is not about just an instrumental category. While in The United States and Brazil the Afro-Americans or Afro-Brazilian identities are profiled, according to the case, in Cuba almost nobody is defined as “Afro-Cuban”, what doesn’t mean that there is no awareness about the importance of the African legacy – from the African enslaved women and men and their descendants – in the construction and development of the Cuban nationality. This comes from historical factors. The struggle for independence of the XIX century were born both from the need of obtaining the political emancipation and the abolition of slavery. The initial revolution, led in the Eastern region by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes on October 10th, 1868, intended to separate Cuba from the colonial Spanish Government and also to make slaves free. The abolition of the pro-slavery regime finally arrived in 1886, not only because of the economic unsustainability of that system before the advance of the productive forces in the industrial sphere, but because of the push of the social movements for the elimination of slavery.

The role of the black and mixed-race individuals was decisive in the second stage of the anticolonial struggles, at the end of the XIX century, and it had an integrative orientation from the popular bases of the insurrection. The Cuban sociologist Fernando Martinez Heredia points to that process when stating that “the black people in Cuba became the black Cubans with the revolution of 1895 and the order of the identity was that from then on until today.” And he adds: “For that reason in Cuba to say Afro-Cuban is a serious mistake if one will refer to the most general, to people’s own existence. There is not such, there is Cuban people” and it was “a conquered right”.

In the sociocultural plane, a long time ago, it was being created what Fernando Ortiz called “cross-acculturation”, it is, the union or mixing of the elements contributed by the diverse ethnic components meeting in Cuba that were configuring an own and new identity by means of multiple and complex interrelations.

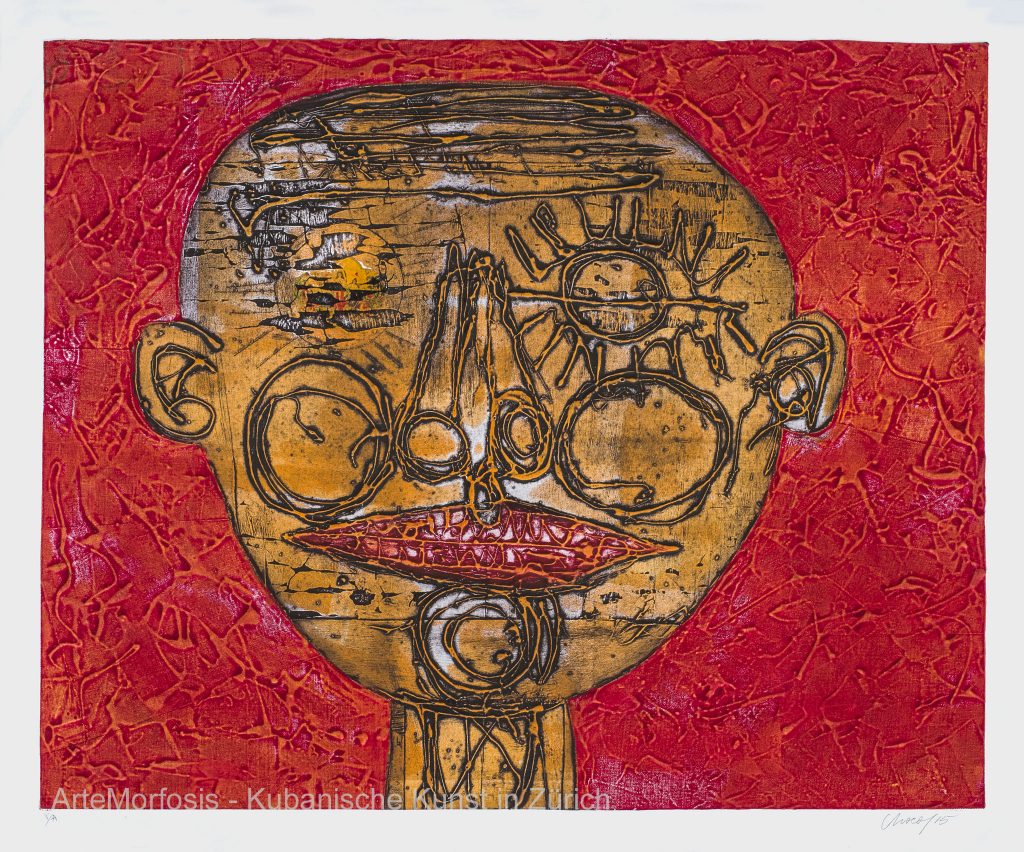

In the history of the visual arts, and the reflection on them of the African legacy, that process went along from an external look of folklore and customs, to an interior, original and conscious look. The first of these looks is contained in the engravings and prints of the XIX century that represented scenes of the urban slavery on squares and streets of the main cities.

It was in the first half of the XX century, after having achieved the independence of the colony, when that cross-cultural reality was evident in Cuban art, what coincided with the assimilation of the artistic vanguards by the artists that starting from these ones began to think about an original way of capturing their sense of their indigenous character. Even though the Western Europe origin of the conventional art practices consecrated by the academic exercises was out of discussion, the truly novel thing consisted on keeping in mind that the Cuban condition would not be complete without the marks coming from Africa and this way to agree with the cultural mixing.

Wifredo Lam (1902 – 1982) was who better understood this, surprisingly from his European experience and his exchanges with the surrealist movement, and his reunion with the insular reality of the 40s of the XX century, when he was forced to quit Paris due to the Second World War. In Havana he painted two famous works: “The jungle” and “The chair”. Everything Lam made from that moment on expressed a syncretic conception where the energy and the spiritual environments of the Caribbean cultures unite in an incessant search of the Cuban soul, in which the ethnos reveals his African, European and Chinese tributaries and reaches an integrative dimension. That metaphoric ability is explained by the great Cuban novelist and critic Cuban Alejo Carpentier with the following words written in 1944: “The eyes free of preconceived images or the d’après l’art ways in the Creole way, Lam began to create his atmosphere, by means of figures where what is human, what is animal, what is a vegetable, were mixed without delimitations, creating a world of primitive myths, with something ecumenically Antillean, deeply bundled, not only to the Cuban soil, but to the soil of the whole group of islands. Unaware of the document, his painting with no local anecdote could not have been able to be conceived, however, by any European artist. All what is magic, what is imponderable, what is mysterious in our atmosphere, appears revealed in his recent paintings with an impressive force. There is a certain baroque style in those exuberant compositions, in gravitation around a “central solid axis”.

But Lam was not the only one in assuming the ethnic mixing from the vanguards. Visibly influenced by Gauguin, Victor Manuel Garcia (1897. 1969) painted in 1929 in Paris, “Tropical Gypsy”, and a portrait that summarizes the physical features of the mixed-race character. Many years later Servando Cabrera Moreno (1923. 1981), with his “Havana women”, would deepen that beloved vision that the poet Nicolas Guillen mentioned when pointing out the achievement of the “Cuban color” as a goal…

A work of unavoidable reference in the evolution of the Cuban art is “The kidnapping of the mixed-race women”, by Carlos Enriquez (1900. 1957). It was painted in 1938 and exhibited in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Fine arts of Havana, this painting recycles, starting from a pictorial innovative perspective, “The kidnapping of the Sabines”, by Poussin, locating the anecdote in the rural Cuban context. By using a chromatic gradation that privileges the transparencies, the painter puts in the center a group of mixed-race Cuban women in an action full of sensuality, in which the violence of the passions is foreseen and the Cuban landscape is seen in the distance.

But if it is about artistic singularities it will be necessary to notice the case of Roberto Diago Querol (1920. 1957) that left a significant mark in the second quart of the XX century, in spite of his short life, because he died being only thirty seven years old. Diago’s art is explained by a triple condition: the black pigmentation of his skin, his belonging to a family and social nucleus of remarkable importance in the popular Cuban culture, mainly in music, and his breaking out with the aesthetic academic codes in those he was trained. The spiritual traditions of the slaves’ descendants and the interpretation of Antillean legends are shown in his painting. “The Oracle” (1949) is one of the first pictorial testimonies of the ritual practices of the abakuá secret society, that originated in the imaginary brought to Cuba by the slaves coming from the territory of Dahomey (at the present Benin). Not only in painting, but also in sculpture the aware expression of the Cuban ethnos should be tracked in that stage, in a particular way in two creators that, like Diago, were black, but whose aesthetic ideals were projected toward the inquiry of the Cuban character in the fullest sense in the concept.

Teodoro Ramos Blanco (1902. 1972) sculpted black and mixed-race figures throughout an artistic trajectory that evolved from the academic realism to the modernist stylization, under the guardian shade of Rodin. It is interesting, apart from the inappropriate and euphemistic terminology to refer to the pigmentation of the skin, what the historian of art Luis de Soto said about Ramos Blanco: “Except in what refers to the election of subjects, I don’t think that the ethnic factor is an appreciable element in the Ramos Blanco’s production. We have been able to observe that his works inspired by topics of the black race surpass the mark of what is individual, what is about customs, what is picturesque and what is folkloric and social, mainly revealing the artist’s concern whose realism doesn’t stick to what is adjectival or accidental of the individual, but to the generalization of what is typical, what is substantive in the expressive content of the sculpture.”

Internationally recognized as one of the masters of the sculpture in last century, Agustin Cardenas (1927. 2001), although he developed his career in Europe, came from Cuba, where in the 50s he contributed with his talent to the irruption of the abstractionism. But as the poet and essayist Nancy Morejón remembers, the topic of identity was not ignored by Cárdenas, but “that ancestral feeling that makes him a rich relative of the anonymous tradition of a multiple Africa” is channeled in the subtle plots of the European modernity.

For the historian of the art Yolanda Wood the Cuban identity profile should not be seen only in the limits of what some people call “raciality”. That is why she draws our attention to another way to reflect ethnos: the vision of the popular culture. As examples of that, she invites to admire two works by Eduardo Abela (1891. 1965): “The comparsa” and “The rumba”. About the last one she writes: “It is revealing a presence not already of the black people, but of what is black in Cuba, as an essential component of the culture.”

From the second half of the XX century to our days that “essential component” has been multiplied in the Cuban visuality to such a point that it deserves another comment that we promise to Artemorfosis’ friends in a future article.