– Virginia Alberdi Benítez –

– Art Critic –

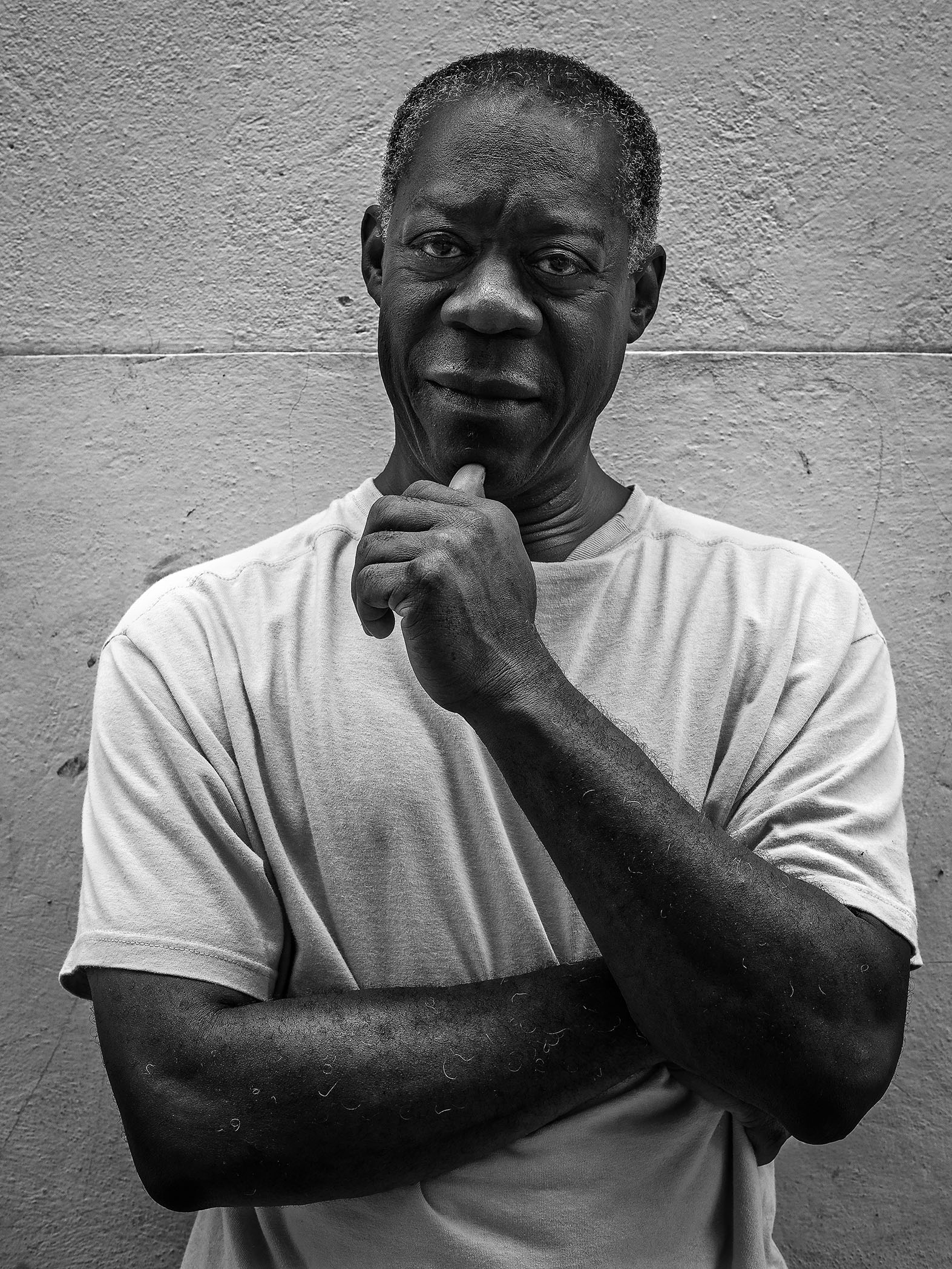

Choco, the renowned Cuban artist, shines with his own light. Perhaps not all inhabitants of the Caribbean island know that his name is Eduardo Roca Salazar, but when you say Choco – the familiar name with which he signs his pieces – Cubans understand that you are speaking of a well-known artist. It is not necessary to be familiar with his work in detail or to frequently visit the spaces where he exhibits; in the public domain, beyond the specialized circles, Choco is someone whom everyone admires for contributing to the heart of Cuban culture.

That perception has been forged over time and is supported by the regularity of a consistent artistic output, duly accompanied by reviews and the media. The most influential Cuban critics followed the creator’s work attentively since the beginning of his career. The national television has dedicated programs to him, and a promotional video from a series on some thirty artists from the island has had a significant tenure for years in prime time.

In recent years, two documentaries on his life and artistic career have had notable impact: Choco (2014), by U.S. professor and filmmaker Juanamaría Cordones Cook, and El hombre de la sonrisa amplia y la mirada triste (The Man with the Wide Smile and Sad Glance) (2016), by Cuban filmmaker Pablo Massip.

But the most decisive recognition comes from the forms of interaction that reinforce group appreciation and statements of opinion, originating from Choco’s active participation in Cuban cultural life: not only in activities related with visual arts, but also in other areas of creativity and social events.

It is no coincidence that prestigious writers and intellectuals from various disciplines have issued appraisals of his work and published impressions that endorse a legacy they consider essential for the spiritual heritage of their fellow countrymen.

His participation in salons and biennials, the awards he has received, his mural paintings, the collaboration with dance companies, and the use of his images in shows have contributed to the notoriety of his work and granted visibility to his artistic mark.

To this must be added his early and subsequently growing recognition in international circles. Gallery owners and art collectors were captivated by the artist as he became known in Latin America, Europe, the United States, and Japan.

As if that were not enough, his work and life coherently complement the artist’s personality. The human being and creator merge in a sole entity. This was perceived in the early days by the great poet Eliseo Diego, who in 1976 wrote, “Eduardo Roca has stopped promising and is already a painter from head to toe. But although his feet are well placed on the ground – in his country – and the head is clear and held on high, it is from the heart that his painting emerges.” And it was confirmed in 1999 by novelist, essayist and politician Abel Prieto: “Choco, unlike others, turns a youthful fifty, without bitterness, with his smile intact, delivering his friendship and his work with the generosity of men; of true artists.”

To decode Choco and understand why he is a prophet in his land and in many other places, one must search into his roots, his aesthetic ideas, and the context of his evolution.

One cannot explain the artist without the social and cultural transformations that took place in Cuba after the change of regime in 1959. The opportunities for personal fulfillment for a Cuban of humble origin born in 1949 were limited. His first years were spent in Santiago de Cuba, the island’s second most important city, located in the eastern region.

As a child he would draw in the school notebooks. A teacher became aware of his skill and encouraged him to answer a call to train the first art instructors. A school had been opened in Havana that rapidly prepared young people from all over the island with the mission of teaching fine arts, dance, music and theater in cities and countryside, schools and factories, military units and fishing villages. That educational effort in 1961 coincided with the massive literacy campaign that taught tens of thousands to read and write in scarcely eleven months.

After two years Choco graduated as an art instructor in visual arts. He recalls his arrival in Havana with a wooden suitcase and the entrance to the school, located in a luxury hotel in the neighborhood that until a short time earlier had been inhabited by the national bourgeoisie. He was the youngest student, and because of the color of his skin his classmates began to call him “Chocolate”, which was gradually shortened to “Choco”.

Since he was only fourteen years old when he graduated in 1963 he was not legally allowed to work, so he was able to continue his studies at the recently opened National School of Art (ENA), in Cubanacán.

The ENA teaching staff in Choco’s day (he graduated there in 1970) included distinguished representatives of the Island’s artistic vanguard. One of these professors was Antonia Eiriz, who exerted great influence upon the first graduates to whom she transmitted the secrets of the craft and the encouragement to develop their own personalities. Another important artist who taught him was Servando Cabrera Moreno, of whom Choco has said, “Without Servando, neither I nor many of my contemporaries would have arrived at the conceptions on art we have today. Servando greatly widened our expectations as painters.” And although painting was in the center of the training, Choco had already come in contact with printing techniques. This, as we shall see later, was providential for the future development of his career.

From Havana he briefly returned to Santiago de Cuba where he worked as a teacher. He moved back to the Cuban capital in 1973, where he settled and dedicated himself to teaching, first in the San Alejandro Academy, and later at the ENA. In the mid-seventies he began to visit the Experimental Graphics Workshop at the Plaza de la Catedral of Havana, where he developed as an engraver until becoming one of the undisputed masters of the specialty.

The painter from the 1970s became well known for his canvases of popular epic themes shared at the time with several of his contemporaries: anonymous heroes of the sugarcane harvest, peasants tied to their land, landscapes transformed by human sensibility.

Regarding those avatars, two events should be taken into consideration. First, his stay in Angola in 1978 as collaborator of the Cuban Civil Mission in the field of culture, which enabled him to obtain direct knowledge of a reality interconnected to his ethnic origins. In addition, there was the beginning of his international career, particularly his emergence in the United States in 1981, when he shared an exhibition with the painter Nelson Domínguez in San Francisco. This is not fortuitous: Choco is one of most popular contemporary Cuban artists in the United States, even before earning the Grand Prize at the Fourth International Print Triennial of Kochi, Japan in 1999, which undoubtedly increased the value of his work.

Since the 1980s Choco evolved stylistically toward the definitive symbols that characterize his images. In general, a reference to take into consideration was the inevitable influence the New Figuration aesthetics exerted not only on him, but also on the early promotions of artists trained at the ENA.

It is worth mentioning that it was not the assimilation of the European criterion of this trend, which included Irishman Francis Bacon, Frenchman Jean Dubuffet, and Spaniard Antonio Saura, but the proximity to the Latin American trend, led by Venezuelan Jacobo Borges, Mexican José Luis Cuevas, and Argentinean Antonio Berni, among others. The latter, by the way, was promoted in Cuba by Casa de las Américas. In his expressionistic version, the neo-figuratism in the Island reached one of its peaks precisely in the work of Antonia Eiriz.

If our artist shows a connection with certain principles of the New Figuration to some extent and in a tangential manner, that is because when observing his paintings and prints one notices the importance of the recovery of the iconic representation and the relation between the human figure and the construction of the painting space itself.

Unlike the generation of artists who emerged in the 1980s, however, neither Choco nor his generational companions dedicated, even remotely, energy to theoretical discussions. They painted, drew, and printed according to their own expressive needs. And if initially they seemed to respond to a spirit of the times, they went on to choose their paths individually resulting from experiences and personal possibilities. In Choco’s case, these experiences nourished his creative impulses and extracted an essential connection that is present in all his work, which the artist has established with the Cuban nationality.

Choco thinks visually what the island’s major poet, Nicolás Guillén, called Cuban color. Neither African nor European, neither black nor white; the artist reflects the result of a new identity, qualitatively different from the ones supplied by the sources. As Guillén stated in 1931, “To begin with, the spirit of Cuba is racially mixed…” and considered that “From the spirit to the skin will come the definitive color; some day it will be called Cuban color.” From the late twentieth century into the present one Choco has faithfully and masterly interpreted the transition from that anticipation to a latent reality.

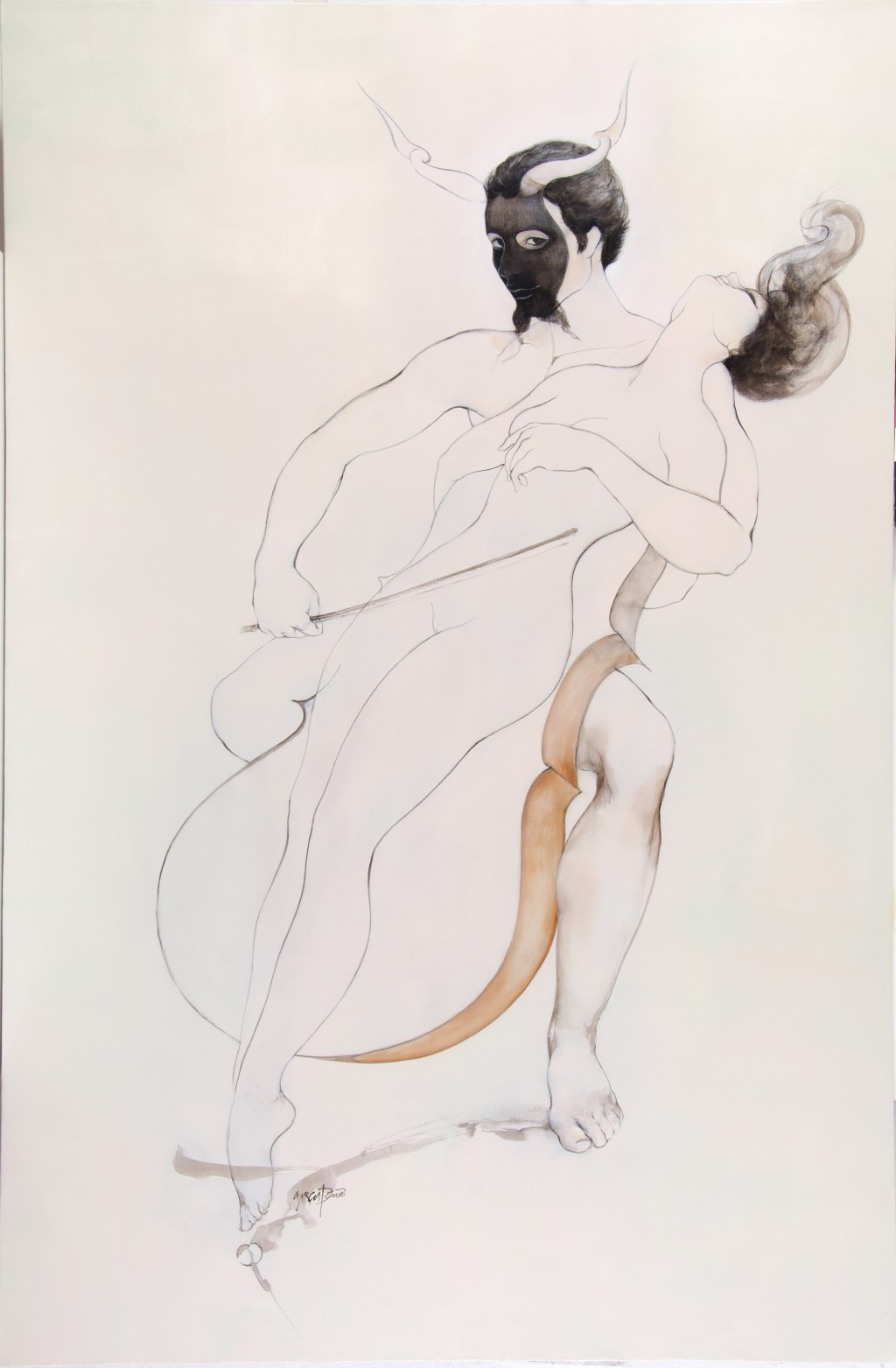

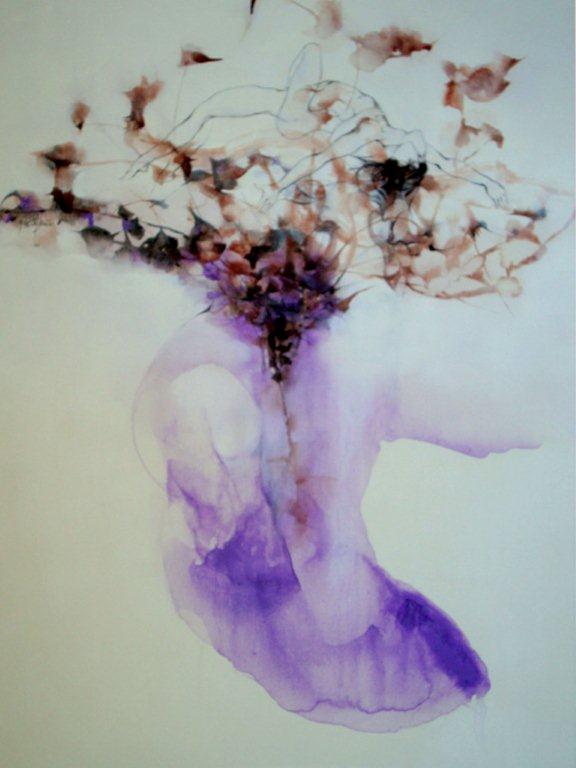

That is evident both in the physical features of his human figures and in the skin textures and atmosphere of each composition. To verify this, examine the repertoire of images displayed in ArteMorfosis gallery. The pieces exhibited there have been recreated in impeccable prints, his well-known collagraphs that are true masterpieces. People crowned by birds, fruits, and hats; faces of mineral consistency that glow with earthly colors; women distributed in space; a dancer of irradiating gesture; a Venus that is saved from original sin; each and every one of them on backgrounds of abundant textures. His painting, with figurations related to the ones in his prints show his mastery of this art form. The polychrome sculptures burrow into the wood for the mystery of plant fibers.

From a technical point of view, the viewer of the exhibited works could ignore the difference between painting and engraving, since what matters and impacts is the visual outcome. The artist actually assumes both lines of accomplishment without stopping in watertight compartments. The porous nature of the borders between one and the other form is due to the character and dominion of the collagraphic technique and internalization of the latter’s effects on the painting procedures.

Choco is conscious of that crossing. He admitted to Cuban journalist Estrella Díaz in an interview, “I learned about collagraphy, and when I started working with it I saw that I was actually painting, because the technique fitted perfectly with my way of painting. Collagraphy, because of its possible textures, reliefs, and technique of execution, was a very interesting and very contemporary painting form. Therefore, I did not feel I was printing – I felt I was painting.”

Painting, engraving, sculpture: Choco is one and indivisible. He summarizes ancestral wisdom and unyielding vitality. The Yorubas, one of the ethnic groups that contributed to the formation of the Cuban nationality, have a saying: “I am because you are.” That is the key – alpha and omega, beginning and end – of his work.

Havana, September 2016

Virginia Alberdi Benítez (Havana, 1947) Graduate from the Higher Pedagogic Institute Enrique José Varona, 1970. Art critic, editor-in-chief of Artecubano ediciones. During more than twenty years she was a Specialist in Promotion at the National Council for Plastic Arts (CNAP). During five years she was a senior specialist at the gallery Pequeño Espacio, at CNAP. She has curated numerous solo and group exhibitions. Her texts appear as collaborations in La Jiribilla, Granma newspaper, the tabloid Noticias de Arte Cubano, the magazines Artecubano, On Cuba, Acuarela. She has written texts for catalogues of different artists.